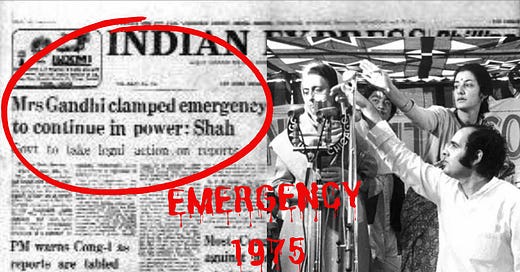

Part I: Emergency 1975: The Attempted Murder of Indian Democracy

Part II: Emergency 1975: Press Censorship, Mass Sterilisation, and Shades of Justice

The Emergency Amendments of the Constitution

The Emergency period witnessed five Constitutional Amendments – 38th to 42nd. Many of them were subsequently invalidated by the Morarji government and the Supreme Court, however, a few changes survived and are in effect till date. The palatable explanation provided by the Indira Gandhi government was to bring changes to meet the aspiration of the people. In reality, the Amendments were focused on centralisation of power in the Prime Minister’s office, discarding Constitutional supremacy, weakening the judicial independence and authority, and giving lifelong immunity from criminal prosecution to the Prime Minister, President and Governors, not only for any crimes done during their tenure, but also before the assumption of office.

The 38th Amendment made the proclamation of Emergency, overlapping Emergency proclamations, and ordinances promulgated by President/Governors, non-justiciable. The 39th Constitutional Amendment was aimed at nullifying the Allahabad High Court verdict that had disqualified Indira Gandhi’s 1971 win on grounds of electoral malpractice, barring her from contesting elections for six years. The Amendment was pushed through swiftly given her Supreme Court appeal hearing on 11th August 1975.

7th August: The 39th Amendment was proposed and approved by the Lok Sabha.

8th August: Approved by the Rajya Sabha.

9th August: Approved by 17 State Assemblies that were specially convened on a Saturday.

10th August: Approved by President Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed, and the government officials published a gazette notice on the same day – a Sunday.

The 39th Amendment retrospectively revised the election law to exclude the judicial purview of the elections of the Prime Minister, President, Vice President, and Speaker, and codified that a court order that sets aside an election of these four functionaries would be deemed void. The move paid off as the Supreme Court of India delivered a unanimous verdict on 7th November 1975, reversing the Allahabad High Court judgement.

The 39th Amendment also placed the Maintenance of Internal Security Act (MISA) into the 9th Schedule of the Constitution, making it totally immune to judicial review, including on the grounds of breaching fundamental rights (thanks to a 1951 Nehru-era Amendment, laws in the 9th Schedule were shielded from judicial scrutiny and could not be invalidated for violating fundamental rights). Incidentally, when MISA was passed in 1971, Atal Behari Vajpayee had said that it was the first step towards dictatorship. In total, the Emergency Indira government sent 47 laws to the 9th Schedule of the Constitution. Apart from MISA, this included The Representation of the People Act, The Monopolies and Restrictive Trade Practices Act, The Foreign Exchange Regulation Act, and The Coal Mines (Nationalisation) Act.

The worst blow to the Constitution came in the form of the 42nd Amendment towards the end of 1976. It arrived when the government had exceeded its five-year tenure, and key Opposition leaders remained imprisoned. The most controversial Amendment in Indian history, it made extensive changes to various parts of the Constitution. Notably, it inserted the words ‘socialist’ and ‘secular’ into the Preamble. Due to its comprehensive nature with over five dozen substantive addition/ deletion/ modification, it was dubbed ‘Mini Constitution’ that established Parliamentary supremacy over Constitutional supremacy. It eroded India’s federal structure by centralising power at the expense of State governments. It introduced Fundamental Duties for Indian citizens. It gave sweeping powers to the Prime Minister’s office, while significantly curtailing the Supreme Court’s power, including determination of the Constitutional validity of laws, and what constituted an office of profit. The Parliament was empowered to amend any parts of the Constitution without judicial review. It basically invalidated the Supreme Court verdict in Kesavananda Bharati case – the verdict that had displeased Indira Gandhi in April 1973, the verdict that the CJI Ray tried to get reviewed by a 13-judge bench in November 1975 but failed. Most provisions of the Amendment took effect on 3rd January 1977, prior to the announcement of general elections.

After winning the 1977 general elections, the Morarji Desai-led Janata Party government undid many changes made by the Emergency Amendments through the 43rd and 44th Amendments in 1977 and 1978 respectively. The 44th Amendment replaced 'internal disturbance' with 'armed rebellion' as the internal criterion for declaring the Emergency, and introduced a string of other crucial safeguards. The Supreme Court, in the Minerva Mills vs the Union of India case in July 1980, unanimously declared that judicial review and a limited amending power were basic features of the Constitution. However, certain provisions introduced by the ‘Mini Constitution’ still remain in effect. For example, Indian political parties are now bound to socialist ideology by the Preamble.

Ideally, both the Morarji government and the Supreme Court should have discarded every single change made to the Constitution by the Indira Government during the period of Emergency. If the subsequent government wished to retain anything from the 38th to 42nd Amendments, they should have reintroduced the same, in a democratically functioning Parliament, with Opposition leaders present to debate the Amendments, and an independent Supreme Court as the watchdog. Unfortunately, neither the Morarji government nor the Supreme Court found it morally repugnant to preserve a single word or alteration made during the darkest era of Indian democracy.

DYK: The 42nd Amendment inserted Article 31D (repealed by 43rd Amendment), which introduced ‘anti-national’ to the Constitution. Article 31D read: “Saving of laws in respect of anti-national activities (1) Notwithstanding anything contained in Article 13, no law providing for (a) the prevention or prohibition of anti-national activities; or (b) the prevention of formation of, or the prohibition of, anti-national associations; shall be deemed to be void on the ground that it is inconsistent with, or takes away or abridges any of the rights conferred by, Article 14, Article 19 or Article 31.

The Shah Commission to Investigate the Excesses of the Emergency Era

The Morarji government appointed Justice JC Shah Commission in May 1977 to investigate the excesses committed during the Emergency regime of Indira. The Commission published its findings in three volumes totaling 525 pages. It declared the signing of the proclamation by President Fakruddin Ali Ahmed as wholly unconstitutional as the advice had not come from the Union Cabinet. The Shah Commission rejected Indira Gandhi’s contention in her letter to the President that internal disturbances posed an imminent danger to the security of India. The Shah Commission stated that the imposition of Emergency was a political decision taken by an interested Prime Minister in a desperate endeavour to save herself from the judicial verdict against her. It outlined Sanjay Gandhi’s actions in Delhi as grave abuse: “Here was a young man who literally amused himself with demolishing residential, commercial and industrial buildings.” The Commission report also outlined the misuse of laws, especially MISA, to settle political scores, and was scathing in its criticism for the subservient bureaucracy.

1st interim report, March 1978: The events leading up to the declaration of the Emergency, the unconstitutionality, and press censorship.

2nd interim report, May 1978: Police actions, the role of Sanjay Gandhi.

The final report, August 1978: Forced sterilisation, prison conditions and custodial torture.

After the second interim report was submitted, leaders of the Janata party began demanding the establishment of special courts for speedy trials related to the Emergency. On 8th May 1979, the Parliament eventually passed an act to establish two special courts, but the government soon fell in July. Charan Singh became the Prime Minister in July end, ironically, with the support of Indira’s Congress. Less than a month later, Lok Sabha was dissolved, but Singh continued as the caretaker PM.

Once Indira Gandhi returned to power in January 1980, her government recalled and destroyed the copies of the Shah Commission report to ensure that it did not become public. The Supreme Court ruled that the special courts were not legally constituted, resulting in no trials ever taking place. The bureaucrats indicted by the Commission went unpunished. The prosecution of Indira Gandhi and Pranab Mukherjee over their refusal to testify before the Shah Commission was quashed in December 1979 by the Delhi High Court over technical/ procedural/ scope issues. You can read the judgement here. In short, nobody was held accountable and punished for derailing democracy.

In 2010, former MP Era Sezhiyan, traced the report, and published Shah Commission Report: Lost, and Regained. Sezhiyan praised the report as “a magnificent historical document to serve as a warning for those coming to power in the future not to disturb the basic structure of a functioning democracy.”

Also in 2010, an RTI application was filed by MG Devasahayam (who was Deputy Commissioner of Chandigarh during the Emergency, and had Jayprakash Narayan in his custody for six months) to get the original paperwork related to the proclamation of Emergency. His application was sent from the Prime Minister’s Office to the Home Ministry to the National Archives. Kuldip Nayar, who was one of the journalists arrested for opposing the Emergency, wrote in August 2010 that the UPA Home Ministry denied having the proclamation of Emergency issued by President Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed as well as any record of the decisions taken on the arrests of over one lakh people. Nayar labelled it as a Congress attempt to cover up its misdeeds. In December 2010, the National Archives released the records due to potential penal consequences for blocking information. While the signature of President Ahmed was present on the proclamation, there was only a typed, unsigned copy of Indira’s letter to the President recommending declaration of Emergency. According to the RTI response, the original letter was probably taken out and was in Gandhi family’s control. Do read this news report to understand the extent to which the Nehru-Gandhi dynasty and the Congress party went to distance Indira from the Emergency.

Forgetting the Lessons

The people chose to forgive and forget the darkest era of independent India. Yes, Indira and Sanjay lost their seats, and their party lost the 1977 elections, losing nearly 9% vote share and not managing to win a single seat in UP, Bihar and Haryana. Its tally reduced to 154 seats from 352 in 1971 – 154 constituencies, 92 of which were from the four Southern States, thought it was okay to elect representatives of a political party that tried to murder Indian democracy, imposed forced sterilisation on people, committed many atrocities, and jailed over a lakh opponents of the regime, many of whom languished in jail till the Morarji government took over. That is 28% of the total seats in the Lok Sabha. In Tamil Nadu, its vote share nearly doubled from its 1971 figure. So, the Southern States did not mind the Emergency much. Two other big States, Maharashtra and Gujarat, gave mixed responses. People in the Hindi heartland, who faced more excesses, especially forced sterilisation, were the ones to express anger electorally.

As a teenager interested in understanding that era, whenever I talked about Emergency with people who lived through it, amid negatives, there were also ‘positives’ – no cows on the roads, trains ran on time, government offices functioned well, etc. They were completely oblivious to the fact that those things, which should be anyway demanded from an elected government, came at the cost of democracy and individual freedoms. No wonder then that in the 1980 general elections, just three years after lifting the Emergency, Indira Gandhi was back in power with a thumping majority, and almost the same number of seats and vote share as in 1971. Congress supporters cite that as a reason to stop talking about the dark era of Emergency because the voters obviously forgave Indira and brought her back to power. To them, the 1977 result was the punishment, and the 1980 result was the absolution of Emergency Indira.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi and the BJP have time and again brought up the Emergency era, and paid homage to those who fought the Emergency. However, the same Modi government conferred Bharat Ratna on Pranab Mukherjee, a Minister of State in the Emergency Indira government, who was indicted by the Shah Commission for misuse of power, and saved from prosecution merely on technical grounds. Given that Sanjay Gandhi’s wife and son are in the BJP, his role as an extra-constitutional authority during the Emergency has not been discussed much by the BJP either – accused of grave abuses by the Shah Commission, Sanjay Gandhi occupies a prime ‘samadhi’ space in Delhi, and has national parks and State government schemes named after him even now, although he was just a Member of Parliament. Many of those who were jailed by Indira Gandhi’s Emergency regime had long buried the hatchet and formed political alliances with the Indira Congress – Lalu, Mulayam, Karunanidhi, Nitish, etc. The message has been crystal clear – politics over a principled stand. But then, politicians also come from within our society, and they often prioritise political expediency if the voter base does not strongly oppose it.

Rahul Gandhi did call the Emergency imposed by his grandmother a ‘mistake’ only to gloss it over by stating that the current BJP setup is worse than the Emergency era. As usual, he provided no evidence to support his claim. In reality, the Gandhis or their political outfit did not learn any lessons from the Emergency, or even regret it much. Priyanka Gandhi Vadra proudly gets compared with grandma Indira, clearly indicating that the blot of Emergency does not weigh in their minds. As the CM of Madhya Pradesh, Kamal Nath, issued a diktat to health workers to bring men for sterilisation or face penalty – reminiscent of the Emergency era. The order was retracted after some outrage, but the media moved on to the next thing instead of grilling the CM or his political party over such a diktat.

While we excessively scrutinise the political class and their potential dictatorial tendencies, we must not overlook the media, the judiciary and the people. In the current context, censorship is no longer necessary to influence the media's narrative. Most media outlets willingly adopt a partisan stance if it aligns with their financial interests or ideological leanings. This is so widely known that it hardly requires elaboration.

The judiciary did not consider it as its moral responsibility to take suo moto action against those responsible for the mutilation of the Constitution and rampant violation of human rights during the Emergency period. The judiciary has been overcompensating since, for its failures related to the Emergency era. In 1993, the nine-judge Supreme Court bench introduced the Collegium system in the Second Judges case verdict. It altered the Constitutional provision of “in consultation” with the CJI to “in concurrence” with the CJI and the Collegium. Over nearly four decades since its spinelessness against the Indira Gandhi government, the apex court has not only asserted its independence, but also assumed a lot of power, which it enjoys with very little accountability. So, while the Emergency era tried to significantly reduce the powers of the judiciary, the judiciary responded by positioning itself as the moral compass and the torch bearer of civil liberties – a higher pillar of democracy – that must not be questioned. In an ironic turn of events, the judiciary is now trying to reduce the powers of the elected government by trying to govern through judicial activism and verdicts, and focusing more on being perceived as independent (read anti-government) than doing its job of dispensing justice (where it fails miserably many times). It tries to play the role of an Opposition through verbal remarks that do not make it to the judicial orders but make media headlines nonetheless.

There was no popular demand to disband Indira’s Congress and ban her politically for life. She, instead, gained popular sympathy over Morarji government’s (pathetically botched) efforts to make her pay for her sin. She continues to be a Bharat Ratna. I am among those very few people, who find it unacceptable that a person who authorised subversion of democracy and flagrant violation of human rights and freedoms for personal power gain, is undeserving to hold the nation’s highest honour irrespective of any good things she might have done during her long tenure as the Prime Minister.

The prevailing state of affairs is marked by political party supporters advocating for stringent actions against their political or ideological adversaries. This sentiment of somehow, anyhow, silencing the opponents, finds takers across the political spectrum. Governments and political parties are liberal in filing legal cases against individuals who criticise the leadership. Between 2016 and 2019, the Kerala Government had booked 119 people for posting objectionable comments on social media against Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan. One can only wonder what the tally is now. In May 2022, Marathi actor Ketaki Chitale was arrested and jailed in Maharashtra for 40 days over an alleged derogatory post on Sharad Pawar (his party was in power in the MVA alliance in the State). The misuse of police and the suppression of dissent is common in the States across India. Some political parties are far worse than others, as they even use political goons to silence people. The freedom of expression is supported or opposed depending on who is the victim. The judiciary is equally averse to criticism – it freely wields the weapon of contempt of court. The desire for instant justice has taken roots among people – be it extrajudicial encounters because the law and order fails to deliver in timely manner, or bulldozer politics (for the record, I support demolitions if due process of law is followed to demolish illegal structures pro-actively as a consistent stand against encroachments rather than a retaliatory measure for some criminal act).

The dark era of Emergency became a mere footnote in our democratic discourse, little known to the present generation and likely to be forgotten by the next. There are elements within all pillars of our democracy that crave unaccounted power. And we, the people, are prone to forgiving, and somewhat embracing undemocratic measures, particularly when they serve the interests of the political party we support, whether at the national or State level. We must realise that the pursuit of short-term gains or partisan agendas should never come at the cost of our freedoms and democratic foundations. It is, therefore, important to keep reading about the Emergency Indira era.

I urge you to read, tweet, write, share, and raise awareness about the dark era of Emergency. Together, let us ensure that these facts reach as many people as possible, especially the younger generation, so that we never forget the horrors, and actively work to safeguard our democracy.

X: @semubhatt