Emergency 1975: Press Censorship, Mass Sterilisation, and Shades of Justice

Part II

Part I: Emergency 1975: The Attempted Murder of Indian Democracy

Press Censorship

The supply of electricity to major newspaper offices in Delhi was cut on the night of 25th June 1975 so that they could not print the news about the Emergency or the midnight arrests. The publishing was disrupted for two days. The editor of The Motherland and Organiser, KR Malkani, was the first journalist to be arrested before dawn on the 26th. The Motherland, however, managed to print that night. The staff ensured that the special Emergency supplement about the preventive arrests and suspension of civil liberties was printed, and also rushed to the Delhi railway station early morning so that people leaving for different destinations could carry it across the country.

On 26th June, the pre-censorship guidelines for the media were issued. Media was instructed to not publish rumours, scurrilous and malicious articles or reproduce anything objectionable that had been printed outside India. Violation of government instructions was a crime, and had consequences, including sealing of the press premises, which The Motherland faced.

On 28th June, The Indian Express carried its iconic blank editorial, so did The Statesman. Other publications followed suit. A journalist anonymously placed a smartly worded obituary for democracy in The Times of India. The Indira regime realised that some publications were expressing their opposition to the censorship by leaving blank spaces or publishing quotes of MK Gandhi or Tagore on freedom. On 29th June, the regime issued revised guidelines to prevent the same.

The Chief Press Adviser position was created to censor the news. All newspapers needed to get prior approval for the articles to be published. One of the several guidelines for the press was, “Where news is plainly dangerous, newspapers will assist the Chief Press Adviser by suppressing it themselves. Where doubts exist, reference may and should be made to the nearest Press Adviser.”

Foreign correspondents from The Times of London, The Washington Post, The Daily Telegraph, Christian Science Monitor, and The Los Angeles Times were expelled. Some foreign correspondents, including that of The Guardian and The Economist, left India upon receiving threats. The BBC called back its correspondent Mark Tully. The Indira government also withdrew accreditation from over 40 Indian reporters and arrested over 200 journalists. Kuldip Nayar of The Indian Express was arrested for organising a pro-democracy protest. In May 1976, the Home Ministry informed the Parliament that 7,000 persons had been held for circulating clandestine literature opposing the Emergency.

Almost all mainstream dailies, with the exceptions of a very few like The Indian Express and The Statesman, succumbed to the censorship. Many smaller newspapers, magazines and journals put up a brave fight – Freedom First, Frontier, Himmat, Janata, Mainstream, Neerikshak, Organiser, Panchjanya, Rashtradharm, Sadhana, Seminar, Swarajya, Tarun Bharat, The Motherland, Vivek, Yugdharm, etc. Most of them were censored and/ or banned. Prominent media figures like Arun Shourie and VB Verghese were forced out, and the regime placed its favoured people on the boards of newsgroups. Congress MP Amar Nath Chawla was appointed on The Times of India board, Kamal Nath on the Express group board. The Hindustan Times owner KK Birla, who was a supporter of Emergency, was made Chairman of the Express group.

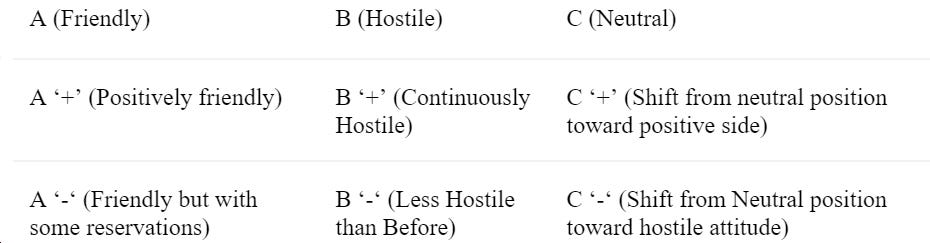

The news flow was fully controlled and the media was turned into a propaganda and misinformation tool in a manner that would have made Goebbels proud. The government advertisement policy was revised to reward the media lapdogs and punish those who refused to bend. The Principal Information Officer of the Indira Gandhi Emergency regime was tasked to categorise newspapers as friendly, neutral and hostile:

The Indian Express and The Statesman were under the B category (hostile). The Times of India, Hindustan Times (and its Hindi newspaper Hindustan), Amrit Bazar Patrika and The Hindu were under the A+ category (positively friendly). Hostile publications lost government advertisement revenue. Positively friendly publications were paid far more than the prevailing rates for advertisements. Even though its circulation had fallen steeply, The National Herald made thrice as much in 1976–77 than its advertisement earnings in 1974–75.

After the Emergency was revoked, LK Advani had addressed the media and said, “You were asked only to bend, but you crawled.”

Mass Sterilisation

Indira Gandhi's son, Sanjay Gandhi, spearheaded a mass sterilisation campaign aimed at population control. This campaign involved the forced sterilisation of people, resulting in severe human rights violations and tragic deaths.

Sterilisation quotas were enforced on politicians, government servants, policemen, and municipal employees. Failure to meet these quotas had consequences. Nobody wanted to upset Sanjay, who wielded immense power, so they did whatever it took to meet their targets. People were made to comply by issuing threats, withholding of salaries, job loss ultimatum, use of force, etc. There were incidents of police forcefully taking the men to surgery to ‘The Camp’ (the term used for sterilisation centres). Khandu Genu Kamble, a sanitation worker at the government hospital in Barshi, Maharashtra, was asked to undergo a vasectomy or else quit his job. He chose to keep his job.

Some states like Uttar Pradesh, Delhi and Haryana, driven by a desire to gain favour of Sanjay Gandhi, significantly exceeded the sterilisation quotas set by the government by ruthlessly forcing sterilisations on even a much younger and unmarried demographic. The UP quota was set at 0.4 million by the Centre for 1976-77, but the State revised its quota to 1.5 million.

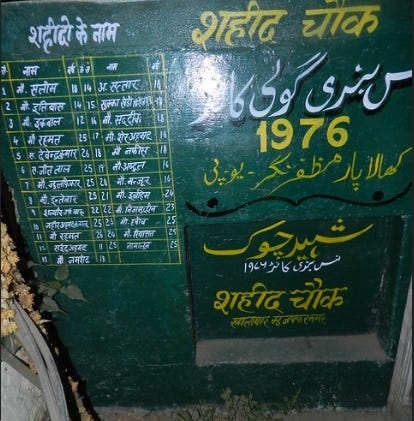

There were numerous incidents of the atrocities committed during that period. Then there was the infamous ‘nasbandi goli kand’ in Muzaffarnagar’s Khalapar where 25 men, including 23 Pasmanda (backward caste) Muslims, and two Hindus who were passing through the area, were killed. On 18th October 1976, a thousand or so Muslims had come out to protest against the forced sterilisation as it was against their religion, and especially as the authorities were forcefully sterilising even young Muslim men. The District Magistrate ordered firing on the protesters. 19-year-old Mohammad Saleem fled his house to escape a visit to ‘the Camp’, but fell victim to police firing. To justify the firing and the killings, the police asked the local Hindu population to give it a communal angle by registering a complaint that Muslims started the firing, but the Hindus refused to do so. The next day, police firing in Kairana village resulted in four more deaths. As was the trend during the Emergency, no FIRs were filed. While that DM retired in 2008 as chairman of the UP Vigilance Commission, the families of the victims never received justice or compensation. They blame their own community leaders who refused to fight because of their proximity with the Congress.

Shaheed Chowk, Muzaffarnagar: 25 victims, including children, of police firing.

After it came to power, the Janata Party government had set up a single-member inquiry commission headed by retired Allahabad High Court Judge Ram Mishra. However, its report was never tabled in the UP Assembly. When an RTI was filed about the inquiry commission report, the authorities replied that it was lying in an almirah whose key had been lost.

In 1976-77, 6.2 million Indians were sterilised in just a year. Some reports put it to as high as 12 million. To put things in perspective, the Nazi sterilisation program sterilised an estimated 300,000-450,000 people from 1934-1945. The Emergency regime of Indira Gandhi achieved 15 times higher sterilisation targets than Hitler, that too in just one year against a Nazi decade, by giving nasbandi targets to Congress party people, local administration and a free hand to the police to use force to get men to cooperate. The pace of sterilisation was so fast that neither the hygiene of the operation theatres was maintained nor were there many follow-ups. It is reported that nearly 2,000 people died from botched nasbandi operations.

In an interview, Indira Gandhi not only agreed that intimidation and coercion were used for mass sterilisation, she justified the same.

Show of Spine by the High Courts, Surrender by the Supreme Court

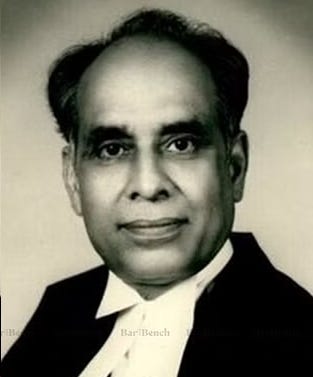

Many cases were filed in the High Courts and the Supreme Court against the preventive arrests made by the Emergency regime of Indira Gandhi. Nine High Courts ruled that the judiciary could entertain habeas corpus writ even after the proclamation of Emergency. However, the Constitution bench of the Supreme Court overruled the High Courts in April 1976 in the ADM Jabalpur case, also known as the Habeas Corpus case, by a majority of 4:1. Chief Justice of India (CJI) AN Ray, Justice MH Beg, Justice YV Chandrachud (current CJI’s father) and Justice PN Bhagwati accepted the Indira government's stand that the fundamental rights, including the right to life and liberty, are suspended during Emergency.

Justice YV Chandrachud noted, “I have a diamond-bright, diamond-hard hope that such things (custodial torture or killings) will never come to pass.” Justice Beg stamped his approval of Indira’s Emergency regime, “we understand that the care and concern bestowed by the State authorities upon the welfare of detenus who are well housed, well fed and well treated, is almost maternal.” The only dissenting voice was that of Justice HR Khanna.

The New York Times wrote: If India ever finds its way back to the freedom and democracy that were proud hallmarks of its first eighteen years as an independent nation, someone will surely erect a monument to Justice HR Khanna of the Supreme Court. It was Mr. Justice Khanna who spoke out fearlessly and eloquently for freedom this week dissenting from the Court's decision upholding the right of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi's Government to imprison political opponents at will and without court hearings.

Justice Khanna had mentioned to his sister that his judgement is going to cost him the Chief Justice-ship of India. Nine months after his dissent, he was proven right, and was superseded in favour of Justice MH Beg.

Let me point out some interesting, but lesser known facts:

Justice AN Ray superseded three seniors to become the CJI right after the landmark 7-6 Kesavananda Bharati v. State of Kerala judgement in 1973, the judgement that greatly displeased Indira Gandhi. Justice Ray, along with Justices MH Beg and YV Chandrachud, was among the six dissenters, with Ray and Beg not even signing the judgement, along with two other judges (including Justice KK Mathew, father of Justice KM Joseph, who retired as a Supreme Court judge recently). Justice Ray was perceived as aligning with the government’s position - bank nationalisation and privy purses cases included. CJI Ray was also reported as hostile to lawyers who argued for civil liberties and the condition of the detenus during Emergency.

In 2011, Justice Bhagwati admitted the ADM Jabalpur judgement to be his ‘act of weakness’; although when in the Supreme Court, the man was known to praise those in power.

Justice Beg, who superseded Justice Khanna, was honoured with Padma Vibhushan in 1988.

During the Emergency, CJI Ray suddenly ordered a 13-judge bench to be constituted to review Kesavananda Bharati case. Nana Palkhivala, who was appearing for Indira Gandhi’s appeal, had returned her brief after the declaration of Emergency. He appeared to defend the majority decision in Kesavananda Bharati case on the inviolability of the Constitution’s basic structure by any amendment. Justice Krishna Iyer (the judge who had allowed Indira to continue as PM but took away her voting right and privileges as MP) told Justice KK Mathew that Palkhivala’s submissions were very impressive. CJI Ray got the news, probably from Mathew, and assumed that Justice Krishna Iyer and others had united against the review. On the third day, the CJI suddenly told the packed court that the review bench is dissolved.

Coming back to Justice Khanna, he resigned after being superseded. Later, he refused to head the inquiry commissions set up by the Janata party government to investigate corruption and excesses by the Indira regime. However in 1979, he became the law minister in the Charan Singh government, and lasted just four days, resigning due to an inability to handle politics. He was the Opposition’s candidate for the Presidential election in 1982 (lost to Giani Zail Singh) and was awarded the Padma Vibhushan in 1999 (the Vajpayee government). Interestingly, in the Puttaswamy case which declared privacy as a constitutionally protected right, Justice DY Chandrachud, son of Justice YV Chandrachud, delivered the unanimous judgement of the 9-judge Supreme Court bench that upheld the dissent of Justice Khanna in ADM Jabalpur case. There could not be a better fitting tribute to the lone dissenter than this.

Justice Hans Raj Khanna

The High Courts and the Bar Associations showed more spine than the Supreme Court. The Bombay High Court, under Chief Justice Kantawala, stood out. As a result, its judges were threatened with transfers. Justice Mukhi was ordered to be transferred to the Calcutta High Court. He was keeping unwell, and the transfer news hit him hard. He passed away. The High Courts provided relief to the arrested people by allowing them to get their own food, books, and even visitors. The Bombay High Court once ordered same day hearings of Madhu Dandavate and his wife Pramila who were lodged in different jails, so that the two could meet, even if briefly. It had struck down the censorship order served on the monthly Freedom First.

The Bar rose to the occasion as well. Many lawyers declined to appear for the government in cases affecting civil liberty. Fali Nariman resigned as the Additional Solicitor General. Palkhivala, as mentioned above, refused to represent Indira any further. When an arrest warrant was issued against the then Chairman of Bar Council of India Ram Jethmalani, Palkhivala, Soli Sorabjee and 300 other lawyers appeared for him in court, and the warrant was stayed by the Bombay High Court. Lawyers were ready for pro bono legal fights for people under preventive detentions, facing custodial torture, or press censorship.

While the Supreme Court's capitulation in the ADM Jabalpur case and the reported unbecoming behaviour of CJI Ray painted a dark picture of the judiciary during the 1975 Emergency, the principled approach of Justice HR Khanna and several High Courts stood as beacons of hope, reinstating faith in the judiciary's capacity to protect fundamental rights and uphold the rule of law.

Part III: Emergency 1975: A Haunting Legacy

I urge you to read, tweet, write, share, and raise awareness about the dark era of Emergency. Together, let us ensure that these facts reach as many people as possible, especially the younger generation, so that we never forget the horrors, and actively work to safeguard our democracy.

X: @semubhatt